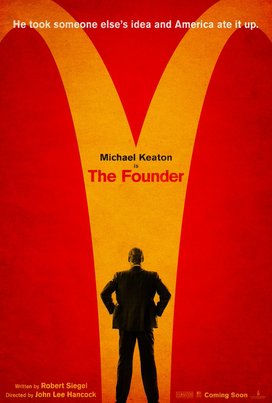

What is also astounding is the company started with a single hamburger stand owned and operated by Dick and Mac McDonald in San Bernardino, California. The brothers opened their establishment in 1940, and it was “revolutionary” (Kroc’s words) in its time as the food was prepared in an efficient assembly line manner. In addition, there wasn‘t an interior dining area or wait staff – orders were taken and customers received their food at the front counter. "Orders ready in thirty seconds, not thirty minutes," Dick says proudly in the movie. When the film begins in 1954, Kroc is a traveling milkshake blender salesman who happens across the restaurant. He immediately sees the franchise potential, and he persuades Dick and Mac to enter into an business agreement to franchise McDonald's restaurants. The brothers sold the McDonald’s Company to Kroc in 1961, and there were already 500 locations in the U.S. by 1963. From a marketing standpoint, I was struck by a few items in the film that have played a pivotal role in the chain’s success:

impede his progress. “That glorious name, McDonald’s – I had to have it,” Kroc confesses. Kroc said the name had a very American sound to it and people could pour their aspirations into it. In comparison, he said “Kroc” wouldn’t have worked nearly as well. It was, by his own admission, too harsh and blunt.

jukeboxes, and drive-in service, and this drew teens prone to loitering and littering. By removing these elements, as well as focusing their menu on simple "all-American" food like burgers, fries and milkshakes, they were able to attract parents and their children. One of the most memorable scenes has Kroc laying out his vision. “McDonald’s can be the new American church!” he declares. “There should be (one) everywhere - coast to coast, sea to shining sea.”

In closing, "The Founder" is an intriguing slice of American history and culture. I was enthralled to watch someone build on the concepts of others and, in doing so, fundamentally change the dining experience both in the U.S. and abroad. There was a McDonald's near my childhood home in suburban Detroit, and I went there fairly often when I was young. So, while I already had a certain attachment to the restaurant chain, the company's legacy truly resonates now that I know the larger story.

0 Comments

Genuineness in marketing seems to resonate in this so-called “information age.” We are, after all, constantly bombarded with a host of material, be it real or fake news, marketing and advertising, and social media (often used to promote said real/fake news and marketing/advertising). Trying to sort it all out can be daunting, so when something comes along that feels bona fide it tends to make an impact. What exactly is “authenticity” in marketing and why does it matter? Lizzie Davey, in her piece “A Beginners Guide To Authentic Marketing,” for tintup.com, describes it as “the process of open communication and being on the 'same page' as the audience you're ‘talking’ to. It's the notion of creating a dialogue between your brand and your audience that's natural and genuine.” Giselle Abramovich, the author of “What is 'Authenticity' in Marketing?” explained the importance of authenticity. Abramovich, writing for digiday.com, said: “We’re clearly in an age of unprecedented consumer empowerment, where the reality of products and services is just a Google search and tweet away. That’s led to an influx of marketers harping on the need to be ‘authentic.’ What’s often left unsaid is what exactly being authentic means within the context of marketing.” One example of authenticity is a recent Yahoo News article I came across about an 11-year-old Girl Scout who sold more than 15,000 boxes of Girl Scout Cookies by "keepin’ it real."

Charlotte’s father, Sean, a producer on Mike Rowe’s “The Way I Heard It” podcast, enjoyed his daughter's reviews and shared it with his boss. Rowe, the former host of TV’s “Dirty Jobs,” read it on air and the publicity that resulted led the younger McCourt to sell thousands of packages.

“In an age of fake news and dubious claims, leave it to a Girl Scout to show us the real value of truth in advertising,” Rowe said in a statement. “The simple truth that not all cookies are created equal. The undeniable fact, that some are ‘divine’ and others taste like ‘dirt.’” How’s that for genuineness? If you can’t rely on the word of a Girl Scout then whose word can you rely on? |

AuthorI'm Eli Natinsky and I'm a communication specialist. This blog explores my work and professional interests. I also delve into other topics, including media, marketing, pop culture, and technology. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed